Mediterranean Garden Society

Mediterranean Garden Society

A Garden on a Rocky Promontory

by Katerina Georgi

photos by Katerina Georgi

Photographs to illustrate the article published in The Mediterranean Garden No. 117, July 2024

The photo at the top of this page shows a view of Katerina Georgiís garden (Photo Katerina Georgi)

Katerina Georgi is Head of MGS Peloponnese branch. She wrties: I came across the old stone house in early 2009. It stood on the highest point of around 1500m² of land, 200m above sea level, with wonderful views of the Taygetos mountain range to the east, and the bay of Messinia to the west. It was built of locally quarried sandstone, had no running water or electricity, and no kitchen or bathroom either. Other than these minor drawbacks the house was perfectly habitable. It had previously been occupied by a single man, allegedly an irascible character, given to resolving disputes by wielding a shotgun. He had clearly lived a spartan life, hauling water from a spring some distance below the house, and cooking in the open fireplace.

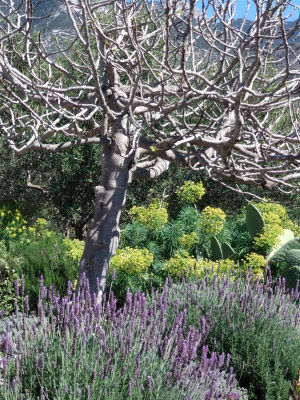

Ficus carica in winter mode, with Euphorbia characias and Lavandula stoechas

The garden consisted of a series of flat terraces enclosed by dry-stone walls. In one corner was a semi-derelict goat shed, replete with rusting chicken wire fencing and sundry detritus. But it also came with a supply of well-rotted manure which was laboriously re-located to avoid contamination during the renovation. The upper levels were solid bedrock, but the lower ones had a reasonable layer of soil and were planted with olive and fig trees.

Renovation of the house began in April 2010, and it was habitable by December that year. The first phase of hard landscaping, a combination of concrete paving and gravel, was completed in tandem with the house, and planting began the following spring.

Antique oil jar with Echium candicans, Euphorbia characias and Tulbaghia violacea variegata

After excavations to lower the ground floor of the house, a thick layer of the resulting sandstone spoil was spread over the bedrock at the upper level of the garden. This was then covered with a layer of gravel to create a new raised terrace and planting beds. This has proved ideal for plants needing free drainage - Origanum dictamnus thrives there, as does Santolina rosmarinifolia.

Salvia rosmarinus, Lavandula, Euphorbia rigida and Ficus carica

The level below this consists of paved areas, a seating pit shaded by a pergola, and an adjoining gravel garden. Most of the paved areas are constructed from concrete cast in situ which incorporates crushed sandstone spoil, so that the colour blends with the walls of the house. Before the paving was laid, topsoil was stripped from the surface, mixed with soil improver, and used to fill the newly constructed planting beds. Elsewhere spoil was used as backfill for new dry-stone walling, and this strategy significantly reduced the amount of spoil to be disposed of.

A stepped 'donkey' ramp now leads down to what had clearly been the vegetable garden, its neatly hoed rows of earth still visible. With the addition of a compost heap, this area was restored to its original function, the sheltered position, lightly shaded by olive trees, being ideally suited to the growing of vegetables.

Plumbago spilling over the steps, with Lavandula, Westringia fruticosa and Nerium oleander in the background

From the entrance, a series of amphitheatrical steps create a diagonal axis, leading to the pool, and the view beyond. Part of the second phase of hard landscaping, along with new raised planting beds, the pool was completed in 2014, and was probably the first of its kind in Greece. While resembling a small conventional pool, it is in fact filtered naturally, without the use of chemicals, and is never emptied. The skimmer is equipped with a lizard ladder, so that hapless reptiles can climb to safety. In fact, they rarely find their way into the pool, except for one Balkan green lizard, which defied all attempts to net it, and completed several astonishingly fast lengths under water before submitting. On summer evenings swallows swoop and dip across the water, unfazed by my presence in the pool. Dragonflies hover, and in the hottest months when water is scarce, bees gather to drink. For several years, the garden was visited by badgers, which drank from the pool at night after hoovering up mulberries. They were beautiful animals, but very destructive, digging large holes, playing havoc with bulbs, and eventually demolishing part of the perimeter wall. Once that was repaired the badgers were unable to visit, but they were soon replaced by boisterous pine martens, equally fond of mulberries, but with a voracious appetite for figs too.

View south across the aloni (threshing floor)

On the lowest terrace is an old threshing floor (aloni) hewn out of solid bedrock. Clearly many years had passed since it had been used to thresh wheat and, over time, a layer of soil and bulbs had built up so that the rock was barely visible. This excess soil was stripped off to reveal the rock, and the bulbs replanted elsewhere. The stone retaining wall on the level above was rebuilt to follow the radius of the aloni, and new steps were constructed on either side to connect the two levels and improve circulation around the garden. I initially scattered Thymus vulgaris seeds, thinking this plant would thrive in the fissures of the bedrock, but they failed to germinate. Since then, wildflowers have gradually self-seeded there, Anemone, Silene and Legousia among them, so clearly there was no need for any human intervention.

Stone steps with Salvia rosmarinus prostratus, Thymus, Lavandula stoechas and Osteospermum fruticans

The planting throughout the garden consists of a limited palette of mediterranean plants, chosen for year-round interest and the ability to withstand drought. The emphasis is on structural planting, and key plants are repeated throughout the garden to give continuity and cohesion. An important criterion is growth habit – specifically the plants’ ability to spread and soften the edges of the hard landscaping, which was initially quite stark but has mellowed with time. I avoid excessive contrast in leaf form and colour, preferring subtle contrasts. The aim is to achieve a calm interplay of colour, form, and texture. Carissa macrocarpa has proved invaluable and never fails to impress visitors. There are several specimens of it in the upper, more formal garden which, with Salvia rosmarinus (formerly known as Rosmarinus officinalis), Cistus and Lavandula, form the backbone of the planting. I'm particularly fond of grey-leaved plants such as Phlomis, Salvia, Helichrysum, Santolina and Artemisia to name a few genera.

The lower area with Salvia rosmarinus, Origanum onites, Lavandula, Teucrium and Euphorbia dendroides amongst the olive trees

In the lower part of the garden, among the olive trees, the intention was to keep the terraces looking relatively natural, so that the planting would blend with the landscape beyond while allowing access for olive picking. Existing specimens of Pistacea terebinthus and numerous self-seeded Euphorbia dendroides are interspersed with Teucrium, Salvia, Origanum and Lavandula. In spring these terraces are awash with wildflowers, punctuated by the striking heads of Allium ampeloprasum, so a path is cut to allow circulation until they seed, and the entire area is then strimmed. This year I was delighted to find Serapias vomeracea in the shade of an olive tree, and hopefully these will multiply.

Festuca glauca, Cistus and Euphorbia characias with borrowed view

Fortunately, there are few pests in the garden, but Hyles euphorbiae, the spurge hawk-moth caterpillar, can be problematic. It has the capacity to strip a mature euphorbia in seemingly no time at all, and consequently grows to a length of 12cm alarmingly quickly. A full-size caterpillar manages to inspire both awe and revulsion in equal measure, and it was no surprise to learn that they are used as biological pest control against Euphorbia virgata, classed as invasive in parts of North America.

The lower level with Oreganum onites, Cistus skanbergii, Teucrium, Salvia rosmarinus, Lavandula and Euphorbia myrsinites

Ultimately, the challenges presented by pests and predators are relatively minor and usually transient. The main issue is inevitably water, and sourcing plants which are adapted to surviving the summer months without it. Recently it has become easier to buy these plants locally or online, but the local nurseries' policy of re-stocking in spring rather than autumn is a source of endless frustration, as planting at that time reduces the plants' chances of surviving the summer. Initially an automatic irrigation system was installed, to sustain the plants through their first summers, but once the plants had established it was removed. New plants are now hand-watered for the first summer or two, and established plants are not watered at all in mid-summer.

The view beyond, with the Taygetus mountains in the distance

In the past, most Greek village houses had a cistern which collected ground water to provide for the needs of the house, and the cisterns generally had a resident eel, believed to keep the water clean. With the modernisation of these houses, the cisterns were frequently turned into septic tanks or soakaways, so that now the houses rely entirely on mains water. In addition, there are increasing demands on the mains supply due to the construction of new buildings, and the higher expectations of their occupants. Unusually, this house had no means of storing water and, having in a previous existence survived several weeks without mains water, I was anxious to avoid repeating the experience. The result is an underground cistern, equipped with a submersible pump, for the storage of rainwater collected from the roof of the house. All that is missing is the eel…

THE MEDITERRANEAN GARDEN is the registered trademark of The Mediterranean Garden Society in the European Union, Australia, and the United States of America