Mediterranean Garden Society

Mediterranean Garden Society

Jacky Tyrwhitt, Remembering an Extraordinary Woman

by Diana Farr Louis

Photographs to illustrate the article published in The Mediterranean Garden No. 113, July 2023

The photo at the top of this page shows Sparoza house in construction (Photo Sparoza archive)

A new job is always nervous-making, but it didn’t help when the young woman showing me around said, “You’ll be sharing an office with Miss Tyrwhitt. She’s quite strict, very British, and we’re a bit scared of her.” I was going to be her assistant, production editor of the esoteric journal Ekistics, the problems and science of human settlements, which she and Constantinos Doxiadis, the noted architect-planner, had founded in 1955, 20 years earlier. My only qualifications were native-speaker knowledge of English and availability.

The moment Miss Mary Jaqueline Tyrwhitt walked into the office, I saw that she was not scary at all, but warm, delightful, funny, and kind. She was thin but wiry and, although her hair was white, she had the face of a sprite, lively and curious. She told me to call her Jacky. Had I known more about her, I would have been in awe, but all she revealed at first, hearing that I’d graduated from Harvard, was that she had been associate professor of City Planning and Urban Design there, from 1955 to 1969, and we had overlapped. Doxiadis had urged her to retire in Greece and, finding the dry climate eased her asthma, she’d bought some land and built a very modern house on a hillside in Paiania, overlooking what is now Eleftherios Venizelos airport.

That summer we became friends, although she was twice my age. I spent more and more time at Sparoza, where she was making a garden of solely mediterranean plants, some native, some smuggled in from her frequent travels. I learned that her early training had been in horticulture, but that she’d switched paths to study urban planning in Germany and in London, travelled on her own on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Moscow, Manchuria and Shanghai, served in the Women’s Land Army during the war. And then took the job she was most proud of: developing correspondence courses for servicemen so that they could jump-start their education in town and regional planning when it was over. These courses were to attract 1,600 students.

I also learned that after the war she’d worked with everyone in the modern architectural/planning scene, from Le Corbusier to Buckminster Fuller (who had designed a small geodesic dome that sat at the bottom of the Sparoza property). But she never talked about them, or her role in the inner core of CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’architecture moderne), introducing ideas and responsible for reports, or her work with UNESCO, or as the “ghost writer” for Siegfried Giedion, CIAM’s Bohemian-born Swiss secretary and an influential critic of art and architecture, who wrote eight books in “unusual English” that Jacky essentially rewrote before they were published.

That was only the tip of the iceberg; because of her remarkable lack of ego, I would only find out the rest of her considerable accomplishments after her death. She never talked about her personal life either, her loves or why she’d never married, but her youthful, witty and thoughtful presence was enough for me.

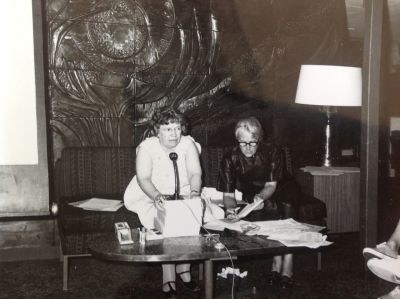

With Margaret Mead on one of the Delos cruises organized by Constantine Doxiadis (Photo Diana Farr Louis)

This was a friend who would give my 8-year-old son a jar full of tadpoles from one of her ponds at Sparoza and then call to find out how they were doing. When I said we’d made the mistake of changing the pond water with chlorinated tap water and they’d all died, she was so upset at thinking how sad he must be that the next day she took the trouble to deliver a new jar of tadpoles to the office, although she was flying out to Vancouver for a Habitat conference a few hours later.

This was a woman who would drive her deux-chevaux through a blizzard to hear me sing in a concert - in the choir, not a solo - and who would scoff when my son, asked to guess her age, said “50?” Jacky retorted, “that’s probably as high as he can count!” She did not let rules stand in her way either. At the Harvard Faculty Club, when the doorman protested that “Ladies were not permitted,” she simply brushed him aside, saying “What makes you think I’m a lady?”

Jacky was also a stoic. I remember one Monday morning she appeared at the office and happened to mention that the traffic had been so awful on Sunday evening that it had forced her car off the road and into a ditch. Despite being battered and bruised, she’d managed to get the car towed and thought nothing of coming into work, even though, at over 70, she was well past the retirement age.

With Panayis Psomoopoulos and other colleagues from the Athens Center of Ekistics (Photo Diana Farr Louis)

One of her great talents was mixing her Athenian/international intellectual friends with her neighbours in Paiania, still country folk in those days. Every Clean Monday, the start of Greek Lent, she would hold an open house and scores of people of all ages would turn up to fly their kites and eat delicious fasting foods. (Jacky was not a cook, however, so we would all bring contributions.) There you would find many colleagues from Doxiadis Associates, musicians from the Contemporary Music Society, and families from the village, some of whom were her students, for she gave a few English lessons. Flying a kite incurred the risk that her goat, Clara, would bring it down; she loved munching on kite twine.

We in turn would invite her to beach parties and Easter lamb roasts in Maroussi, but the party that sticks in my memory was her 75th, held at Panayis Psomopoulos’s house in Athens in 1980. Panayis, a character himself and the ruler of Doxiadis Associates’ Athens Center of Ekistics, had invited half the company. Jacky was tickled pink.

Three years later she would be dead, from complications caused by the heavy doses of cortisone she was prescribed to combat her asthma. Her diary shows that she was working on the next issue of Ekistics until the day before, even though in great pain from a fractured rib.

As we struggled to cope with our grief, her family, who had flown to Greece for the funeral, eased it somewhat by holding an open house and letting her friends choose from among some of her belongings items that would remind them of Jacky. I picked a handsome celadon bowl and a Japanese “house” jacket, which I still wear in summer instead of a bathrobe. Her niece, Catharine Huws Nagashima, and I were then entrusted with preparing/compiling an In Memoriam issue of Ekistics. It took us two years for there were so many people who wanted to contribute, so many stories and photos to put together.

Looking through it now brings back so many memories but reminds me too of how little I knew about this extraordinary person. Just the tip of a very warm “iceberg.” One thing though: as I went through her diaries, I discovered that she never had a bad word to say about anyone, even to herself. Most of the entries had to do with work, her garden and her plants, and the book she was working on: Making a Garden on a Greek Hillside.

This book, which would not see publication until 1998 with drawings by Derek Toms, describes how she turned a windswept hill with a few “sheep-nibbled bushes” into a garden, with chapters organised by month: events, jobs, fauna, climate and flora, with a full description of the plants in bloom, native and introduced, with their Latin and common names. March, for example, includes 55 native species and 13 introduced.

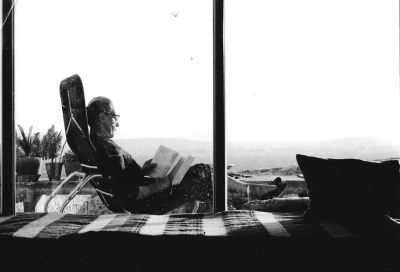

Jacky on the veranda at Sparoza

Her other project, the garden at Sparoza itself, is very much alive. Jacky left it to the Goulandris Museum of Natural History in Kifissia, and under the care of another exceptional and modest woman, Sally Razelou, until her death in 2021, it became more beautiful than ever. It has been the headquarters of the Mediterranean Garden Society, which now has members in more than 40 countries, since its founding in December 1994. Whenever I go there, I almost think I see Jacky behind a shrub delightedly watching her “baby” inspire so many people with joy and appreciation of nature. In Sparoza, her last work, the Mediterranean Garden Society has a living memorial to this citizen of the world who never lost her love of the land and its plants.

As far as I know there is only one biography of Jacky: Jaqueline Tyrwhitt: A Transnational Life in Urban Planning and Design, by Ellen Shoshkes. But her conclusion could not be more true: “[Jacky’s] garden at Sparoza, a living work of art, survives as a lasting tribute to the intellectual, professional, and personal contributions she made throughout her remarkable life.”

This article first appeared in Diana Farr Louis’ column in weeklyhubris.com

THE MEDITERRANEAN GARDEN is the registered trademark of The Mediterranean Garden Society in the European Union, Australia, and the United States of America